Recently I left for the store and forgot my phone. When, a few blocks from home, I realized my phone-free status, I felt instant discomfort, wondering: What if my car breaks down? Then I smiled because—good grief—for most of my life, I always left home without a phone! Not only was I generally okay, but when something went wrong and I needed help, delightful things often transpired. Such as the time I was halfway between northern Oregon and northern California and had car trouble. I happened to be near a rest area I pulled into. There I encountered a man whose last name may have been MacGyver, who brilliantly improvised a fix for my car, sending me on my way (my apologies if you’re too young to know about MacGyver).

The truth is, I fear we’re losing the art of asking for help.

Just weeks ago, I had to knock on my neighbor’s front door. Boy, did I feel awkward. I had walked out to my back yard only to have the latch on my sliding glass door fall down, locking the door from the inside. Since my front entrance was locked and I had no purse, phone, or keys, I was stuck. In order to call my husband, I needed to use the phone of my neighbor. Naturally, he was glad to assist.

That’s the thing, most of us are glad to assist people with needs. We are wired to help one another. So the vibes we get from helping benefit us almost more than the benefits we confer to others. Some might see this as a reason not to help—because of all the conflicted self-aggrandizement wrapped up in our helping actions. But I think that’s the wrong way to look at it. We should look at the good feelings we get from helping not as self-serving, but akin to the feelings of doing something we’re made for—like scoring a 3-point shot, playing an instrument, decorating, writing code, or anything else we’re made for. We are all made to be helpers.

Lately, on occasion, I’ve been visiting the Quaker community my husband is a part of. One of the things I most admire about this community/church is how they normalize asking for help. Through an active email list-serve, people can solicit the borrowing of a tool they need, or ask for moving help or recommendations for a tutor, or giveaway furniture or other items they no longer need. These are small things, and I expect the people in this community still live the relatively independent lives characteristic of American culture. But they are making forays into a sharing economy and opening themselves to the sometimes-awkward exchanges of helping. In the end, these exchanges become less and less awkward.

The church I serve part time as an Episcopal deacon is a Spanish-language community. Congregants are almost all bi-cultural, being from Latin cultures and living now in the United States. For them, helping one another is second nature. The manner of doing so is often invisible and far more informal than among Anglos, who tend to systematize these things. Among Latinos, extended families and “chosen families” figure prominently in sharing economies. They pick up and watch each other’s kids. They bring each other food. They share money and resources when needs arise, and other such actions. But the actions are largely informal and unseen. Sometimes a strict sense of obligation accompanies the receiving of help. If one is helped, they are expected to help back when needed. Yet, this doesn’t seem to stop the flow of give-and-take. For these immigrants, it is simply who they are. How the culture of helping changes as generations enculturate to America, I am not certain.

One of oh-so-many problems with the rising oligarchy in this county is the increasing propping up of billionaires and “self-made men” as the pinnacle, as if being independent of others is ideal—even as we veer into a deepening crisis of loneliness and isolation. But isn’t the veneer of independence really an illusion? To riff on a Jesus-saying: What does it profit a billionaire to have it all, when he must sacrifice his values and self-respect to stay on top?

I am hoping to move in the opposite direction of this trend: more helping and asking for help. More sharing and receiving.

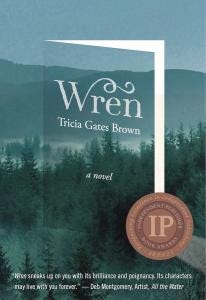

Wren, winner of a 2022 Independent Publishers Award Bronze Medal

Winner of the 2022 Independent Publisher Awards Bronze Medal for Regional Fiction; Finalist for the 2022 National Indie Excellence Awards. (2021) Paperback publication of Wren , a novel. “Insightful novel tackles questions of parenthood, marriage, and friendship with finesse and empathy … with striking descriptions of Oregon topography.” —Kirkus Reviews (2018) Audiobook publication of Wren.